When Will There Be an Answer for Pinkeye?

By Dr. Michelle Arnold, DVM

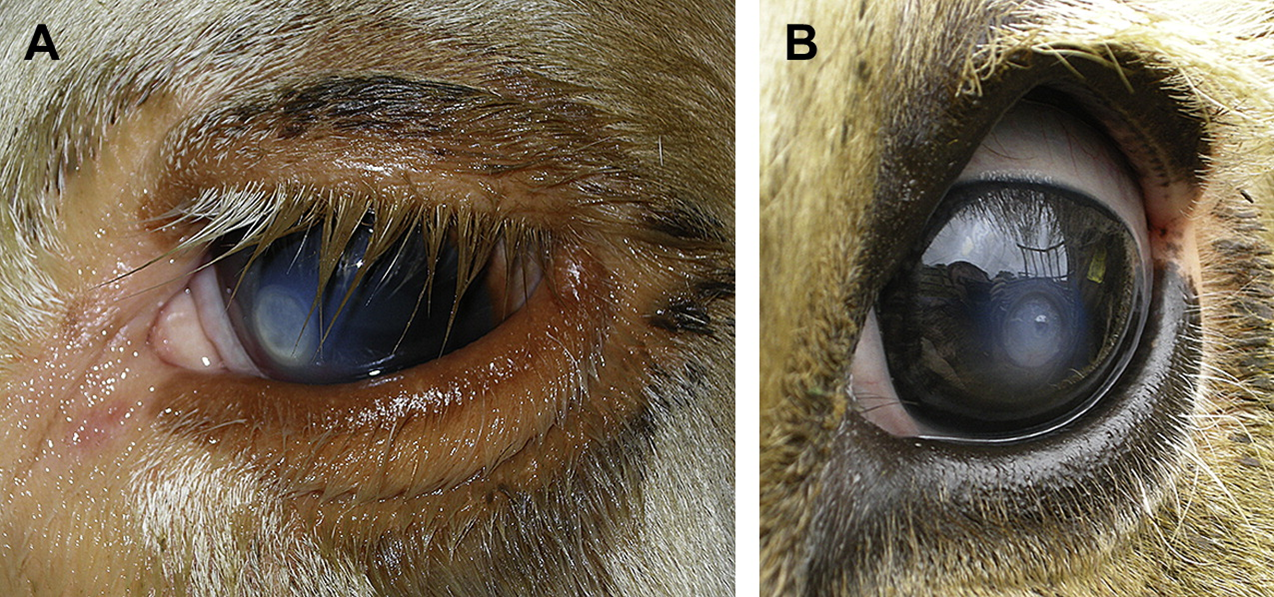

Pinkeye or IBK (infectious Bovine Keratoconjunctivitis) is a costly disease for cattle producers. The cost of treatment coupled with the fact that affected calves wean off on average 15-30 pounds lighter and bring less at the market due to corneal scarring make this disease a significant economic consideration. Despite all we know about how pinkeye develops, control programs are often only partially successful. In particular, pinkeye vaccines seem marginal at best in preventing outbreaks during the summer. It is important to understand that many factors are involved in the development of pinkeye including environment, season of the year, concurrent disease, the strain of bacteria involved, and the animal’s immune system. Once pinkeye begins, it is highly contagious and can spread rapidly within the herd. Careful attention to control of contributing factors and prompt treatment in the face of an outbreak are necessary to reduce the spread and limit the damaging effects of the disease.

It is widely accepted that the most important risk factor in pinkeye is the bacteria Moraxella bovis or M. bovis. It attaches to the eyeball (cornea) by hairlike projections called “pili” and produces toxins that cause the eye to ulcerate and melt (liquefy). It is against this Moraxella organism that we vaccinate with commercial pinkeye vaccine products such as Piliguard, Vision 20/20, Alpha 7/MB-1, I-Site XP, Pinkeye Shield, Ocuguard and SolidBac. One reason for vaccine failure is a recently discovered second strain of bacteria, Moraxella bovoculi, that is now being isolated from pinkeye cases but is not included in any commercial vaccine preparation. Consequently we are not getting full protection against the bacterial causes with commercial vaccines. The two most important contributing factors to pinkeye following bacteria are UV light (sunlight) and face flies, both of which can damage the corneal surface and allow the Moraxella species to attach to the surface of the eyeball and grow. Face flies also serve as vectors to spread the bacteria throughout the herd. One study found the Moraxella bacteria can survive on the legs of face flies for up to three days. Other risk factors that can initiate infection by eye irritation include dust, trauma or injury, wind, tall grass, thick stemmed hay, high ammonia levels and stress. Many different combinations of these factors can occur within one herd at one time. For example, a combination of M. bovis, face flies and sunlight may cause pinkeye in one group of cattle in one pasture while tall grass with seed heads, M. bovoculi, and sunlight may combine to cause problems in another group on a different pasture. In this situation, good fly control and vaccination will significantly decrease the cases of pinkeye in the first group of cattle, but the second group will not show much improvement. This explains why in some years control measures seem to work well and in others they seem to be completely ineffective. Vaccination may reduce the incidence of disease but seldom stops it completely, especially in herds where pinkeye is associated with both Moraxella bovis and Moraxella bovoculi.

As producers, what can you do to prevent pinkeye? The best plan is to reduce or remove as many risk factors as possible in order to keep the eyes healthy and better equipped to fend off disease. An overall good level of nutrition, adequate trace mineral intake, a comprehensive vaccination program, and parasite control are all exceptionally important in improving cattle’s ability to fight off any disease process (not just pinkeye). Prevent eye irritation with good face fly control, mow tall grass, and reduce sources of stress (such as overcrowding/overgrazing) if possible. Control face flies with ear tags impregnated with insecticide and topically administered insecticides by way of back and face rubbers or dust bags they must walk under to get to water or mineral. Provide shade to protect from UV rays. Clean drinking water (instead of stagnant pond water) is critical because the precorneal tear film is essential in eye defense mechanisms. Intake is greater with clean water and this helps provide plenty of fluid in the eye, especially in dry, dusty, and/or windy conditions. Vaccination may prove beneficial, depending on the bacteria involved. In the face of a pinkeye outbreak, preventing transmission is the single most important factor in controlling the disease. Immediate detection and isolation of affected animals coupled with prompt treatment are necessary to reduce the spread and limit the damage to the eye. Long acting antibiotics such as LA-200, Draxxin, Nuflor, and Excede are recommended to treat the infection and can often be effective with a single dose. Treatment also reduces the duration of the carrier stage when recurrence and transmission most often occur. Your veterinarian can take cultures from affected eyes and send the swabs to one of several laboratories that can create a vaccine tailor-made for your farm (known as an “autogenous vaccine”). All cultures must be taken early in the course of disease, preferably when the eye is just beginning to tear (water) excessively.

Pinkeye is a tremendous summertime headache in Kentucky. The keys to prevention of an outbreak are maximizing your herd’s immune status, minimizing the concentration of the Moraxella bacteria, and maintaining an irritant-free environment. Work with your veterinarian to devise an appropriate program for your farm.