Drought-Proofing Your Grazing System

By Chris D. Teutsch, UK Grain and Forage Center of Excellence at Princeton

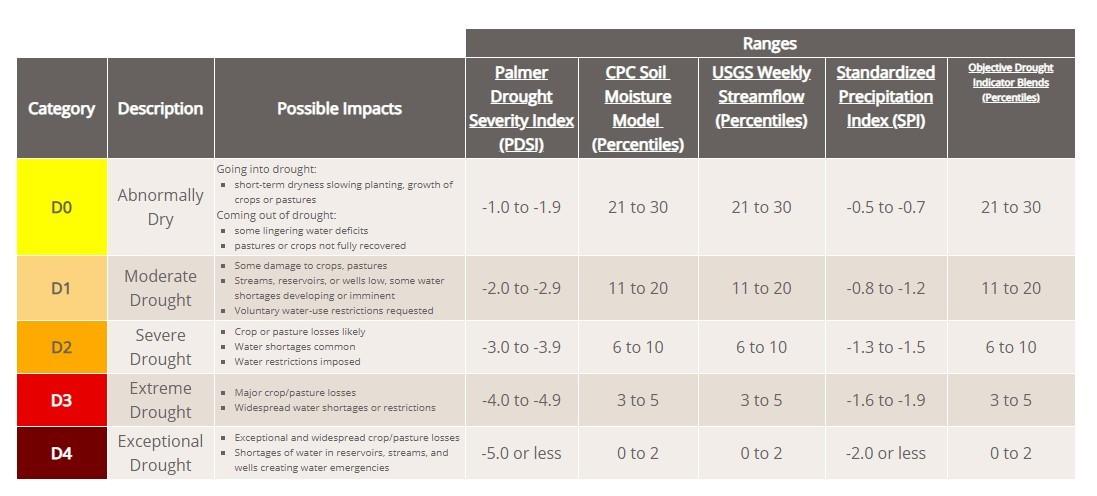

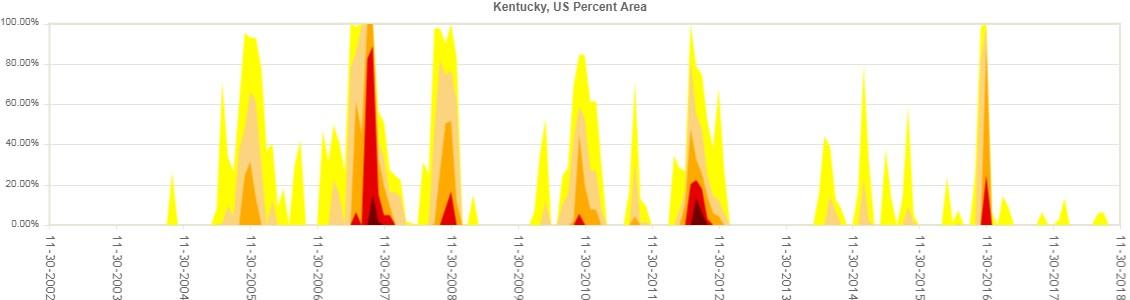

Do you know what the difference is between a flood and a drought? About two weeks! This has been a fairly wet fall. So, it seems a little ironic to be talking about drought when we can’t seem to get the soybeans finished up. However, it is important to remember that drought is a part of Kentucky’s agricultural landscape. Since 2002, some part of Kentucky has experienced a “moderate” drought 11 out of 16 years (Table 1 and Figure 1). “Severe” drought has occurred seven out of 16 years and “extreme” drought five of 16 years. Therefore, drought should not be a surprise, but rather an anticipated and planned for occurrence for grass-based operations in the Commonwealth.

Implement rotational grazing. Although this does not sound like much of a drought management strategy, the first thing that people notice when they switch from a continuous to rotational grazing system is that pastures grow longer into a drought and recover faster after the rain finally comes. The reason for this is that rotationally grazed plants have larger and healthier root systems that can go deeper into the soil for water. In fact, maintaining a healthy pasture is not just a drought management strategy, but probably one of the best ones.

Incorporate deep-rooted legumes into pastures. Interseeding legumes into pastures increases pasture quality, supplies nitrogen for grass, and extends grazing during a drought. The most commonly used legume would be red clover. The primary advantage of red clover is that it has great seedling vigor and can be easily frost seeded into pastures. Alfalfa possesses a deeper tap root and is more drought tolerant than red clover. Alfalfa mixes well with a variety of grasses like orchardgrass and tall fescue. The most drought tolerant legume and our only truly perennial warm-season legume is sericea lespedeza. Sericea has an extremely deep taproot, but its major limitation is poor seedling vigor making it difficult to incorporate into an established sod. Once established, sericea has amazing drought tolerance; however, palatability can be low. Making sure it does not get too tall before grazing is key to maintaining palatability.

Incorporate warm-season perennial grasses into grazing system. During the summer months, warm-season grasses will produce about twice as much dry matter per unit of water used when compared to cool-season grasses. There are a number of perennial warm-season grasses that can used, but in western Kentucky the most productive, persistent, and tolerant to close and frequent grazing is bermudagrass. Bermudagrass requires management to be productive, which means it needs to be grazed frequently to keep it vegetative, and it needs nitrogen. Other perennial warm-season grasses include the native grasses such as big and little bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass, and eastern gammagrass, and Caucasian bluestem.

Incorporate warm-season annual grasses into grazing system. Warm-season annual grasses like pearl millet, sorghum-sudangrass, sudangrass, and crabgrass can provide high quality summer grazing. The primary disadvantage with summer annual grasses is that they need to be reestablished every year, which costs money and provides the chance for stand failure. The exception to this is crabgrass that develops volunteer stands from seed in the soil. Although most people don’t realize (or want to admit it) crabgrass has saved many cows during dry summers in western Kentucky. Research has shown that crabgrass responds well to improved management and can produce 2-4 tons per acre of highly digestible forage.

Irrigate pastures. Irrigating your pastures can increase dry matter production by about 50% in a normal year and much more than that in a dry year. The best grass to irrigate is a warm-season perennial and annual grasses such as bermudagrass and sudangrass. One common misconception is that irrigating a cool-season grass will make it grow in the summer. Cool-season grass growth is limited by not only moisture, but also temperature. Once temperatures exceed 70°F, cool-season grass growth greatly slows and even stops in some cases. In contrast, warm-season grasses do not even reach peak growth until 90°F. Research has shown that warm-season grasses will produce about twice the growth per unit of water used.

Feed hay. The most efficient way to harvest forage is with the animal. In Kentucky we should strive to reduce hay feeding in our grazing systems. This doesn’t mean that we will not ever need hay. Drought is certainly one of those cases that hay will likely be required. A common problem with the hay feeding strategy is that when you need it, everybody needs it and there is little to go around. In addition, the price of hay during a drought can be high. One thing to think about is buying hay during a good year and storing it under cover. It is kind of like having money in the bank. Hay that was well cured will keep for years if it is kept off the ground and out of the weather. A key to successfully using hay is to start to feed it before pastures have been overgrazed. Hay feeding should be done in one paddock so that damage from overgrazing is confined to this area.

Utilize commodities to extend pastures. Commodities such as brewer’s grain, corn gluten, and soybean hulls can be used to supplement and extend hay and pasture during drought periods. Things to consider are the availability, storage, handling, feeding, and price of commodities. The ability to readily get commodities and efficiently feed them is critical if they are going to be a key component in your drought management strategy.

Stock for five-year drought. Having a perpetually light stocking rate that underutilizes pastures in most years but gets you through drought years is a viable drought management strategy. However, this strategy requires that you have a lot of land area and will tend to reduce profit per acre. In most cases this probably is not the best long-term drought management strategy. There is no better way to lose money than under or overstocking your pastures. Set a sustainable stocking rate for the “average year” and focus on other drought management strategies.

Wean and sell calves early. This has a two-fold effect; first it reduces the number of grazing units and the total forage needed, and second it reduces the nutritional requirements of the brood cows. The downside is that you will be selling lighter calves when the prices are low.

Sell cows. This could be a good time to get rid of those older cows that you have been meaning to cull. However, selling your better animals is probably one of the least desirable drought management strategies. If you have invested time and money developing a superior herd, you are probably not real eager to sell those animals when prices could be low. In addition, if you sell off a considerable portion of your herd, it may take years to build back up to that level. However, if this is the management strategy that you have chosen, then you need to sell at the set time. By doing this you may limit losses by beating the flood of animals that typically enter the market as the drought worsens.

Once you have settled on a drought management strategy, it is important that you are ready to implement it in a timely manner. If you are selling cattle, sell them before the price drops. If you are feeding hay, feed it before the cattle lose condition and pastures have been damaged from overgrazing. To accomplish this, you will need to set quantifiable benchmarks. These could be days without rain, available forage on hand, pasture height, pounds of weight loss or change in condition. Regardless of what you have set as a benchmark, you need to be ready to implement your drought plan when you reach it.