Winter Watering of Livestock

As daily temperatures start to decline, most producers begin to focus on delivering stored forages to their livestock. Often, at this time the thought of an animal’s water needs are discounted. However, even in colder temperatures, water requirements of livestock are critical to maintain optimum animal performance. Winter brings the challenge of providing water to livestock while battling frozen plumbing that delivers water.

Water Requirements

An understanding of how much water is required by animals during the colder parts of the year is needed when considering winter watering systems. Factors that affect water intake include: environmental temperature, feed moisture, body size, and level of milk production. A lactating beef cow in the summer on a 90˚F day will drink 16 gallons of water, while during a 40˚F day in December the same cow would consume less, approximately 11 gallons. Table 1 shows the water requirements of several classes of beef and dairy cattle at varying daily temperatures. Table 2 shows water requirements for different classes of goats and sheep.

Table 1. Daily water needs for cattle as influenced by temperature.

| Class | Impact of Ambient Temperature on Water Intake (gallons/head/day) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 40°F | 70°F | 90°F | |

| Beef Cattle | |||

| Growing, 600 lb | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Finishing, 1000 lb | 9 | 13 | 21 |

| Wintering Pregnant Cow, 1000 lb |

6 | 9 | -- |

| Lactating Cow, 900 lb | 11 | 17 | 16 |

| Bull, 1600 lb+ | 9 | 13 | 21 |

| Dairy Cattle | |||

| Dry Cow | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| 40 lb Milk | 16 | 22 | 27 |

| 80 lb Milk | 26 | 34 | 45 |

Adapted from 1996 Beef NRC and UK Publication ASC-151 Pasture for Dairy Cattle: Challenges and Opportunities

Table 2. Small ruminant water requirements.

| Class | Water Requirement (gallons/head/day) |

|---|---|

| Goats | |

| Mature | 1-3 |

| Lactating | 3 |

| Sheep | |

| Rams | 2 |

| 5-20 lb lambs | 0.1-0.3 |

| Lactating Ewes | 3 |

| Feeder Lambs | 2 |

Adapted from Meat Goat Nutrition, Langston University and MWPS-3 Sheep Housing and Equipment Handbook

During cold periods, livestock energy requirements increase to maintain body temperature. To meet the increased energy requirements, animals increase dry matter intake (DMI) if they physically can consume more feed. Water intake affects animal DMI and if it is limited due to a frozen, inaccessible water source, animals will not be able compensate for the colder environmental temperatures. Excessively cold water temperature will also decrease water intake, as well as increase energy requirements by lowering body temperature.

Methods to Deliver Water in the Winter

What is the best method for providing water to livestock during the coldest days of the year? Depending on several factors, different options rise to the top of the list. First, what is the actual water source? Will a pond or stream be used? Are waterers going to be installed? Is rural water available? Surface water sources, like ponds and streams, require a lot of management, especially during freezing temperatures. If water is flowing, such as a spring-fed stream, this task is not as labor intensive. However, if surface water sources are used, one must take steps to ensure that the water quality downstream is maintained and that streambank quality is preserved. For more information on environmental concerns with grazing near these water sources, see the UK publication Pasture Feeding, Streamside Grazing, and the Kentucky Agriculture Water Quality Plan.

Large stock tanks with greater capacity are another option that can be considered. These also need to be checked often to allow livestock access to water. To limit the amount of ice accumulating, a continuous flow valve could be installed to prevent freezing. This also requires an overflow directing water away from the tank to prevent mud.

Is electricity available at the winter feeding site? If so, the number of watering options increases. An electric heater to keep water thawed can be added to almost any watering system. In some cases, this simply might involve adding a plug-in heater that installs through the drain plug of a stock tank. Also, the addition of plug-in heat tape affixed to interior pipes and water bowls of automatic waterers are options that could be considered.

Another option to provide water to livestock when electricity is not available is through the utilization of geothermal heat. A variety of watering systems have been developed to harvest geothermal heat from the ground below the tank, keeping water thawed and available to livestock even in the coldest of environments. Most of these waterers use heat tubes buried deep into the ground, allowing for geothermal heat to rise and keep water supply lines and the drinking trough thawed. While these systems do a good job of keeping pipes and floats from freezing, they are not ice-free. Depending on the amount of animal traffic using the waterer and environmental temperature, there is often a thin layer of ice over the drinking area on very cold days that must be removed.

Producers who continue to rotationally graze throughout the winter months face an even greater challenge in providing water to several locations for their livestock. The frequent moving of animals complicates the use of permanent watering sites from an economic standpoint. With that in mind, grazers must become quite creative to provide water to their animals while maintaining their rotational program.

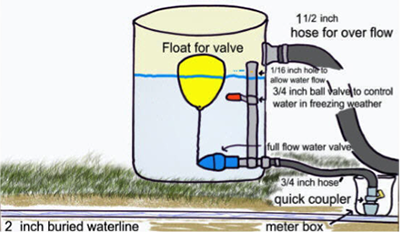

Bill Payne, a producer from Knob Lick and NRCS Technical Service Provider for grazing plans, rotationally grazed dairy replacement heifers extensively throughout the entire year and developed a watering system that allowed him to rotationally graze through the winter. Bill installed a network of two inch waterline to service 80 watering points that are housed below ground in water meter boxes. By utilizing quick couplers at the watering points, he was able to quickly move his water trough to different paddocks as the herd moved. To keep his water trough from freezing, Bill utilized a ball valve installed in a riser pipe above the float valve. When opened, the valve allows water to continuously flow and thus keeps the trough from freezing. He also installed a drain near the top of the trough with a 1 ½” drain hose leading away from the trough to limit mud around the watering area. Bill said that the key to the system is overflow management. As temperatures drop, the ball valve needs to be opened more to prevent water from freezing by allowing more water to flow out of the system. Pictures of the system components are shown in Figure 1, with a schematic of the water trough design in Diagram 1.

No matter which method is used, a clean and consistently available water source is critical. Proper evaluation of where and how to winter livestock could make providing water easier during the coldest part of the year depending on available water sources. For additional information, contact your local NRCS and UK Extension offices.

Categories:

Winter

Animal Management